MY MOONSHOT

“We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things. Not because they are easy, but because they are hard.”

It is easy to forget that in September 1962, the idea of putting a man on the moon was considered to be indulgent and utterly fanciful in many quarters. The response to President John F. Kennedy’s commitment was not universal acclaim, but divided. Kennedy’s predecessor, Dwight D. Eisenhower, declared the plan as “just nuts.”

And yet less than seven years later, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin had walked on the moon and inspired an entire planet, giving way to new etymology around what it means to take risks: a moonshot.

Reversing climate change, curing cancer, ending world hunger, any challenge deemed all but impossible to solve, one that requires the investment of expertise, capital and time, is a moonshot.

The risk of a moonshot endeavour? Setbacks and failure. But without setbacks and failure, and without taking the risks associated with failure, we would never be able to shift the dialogue on the issues we each seek out to resolve. Could a COVID-19 vaccine have been delivered in under a year without risk capital and the collaboration of the world’s greatest scientific minds? Absolutely not. And yet this was achieved.

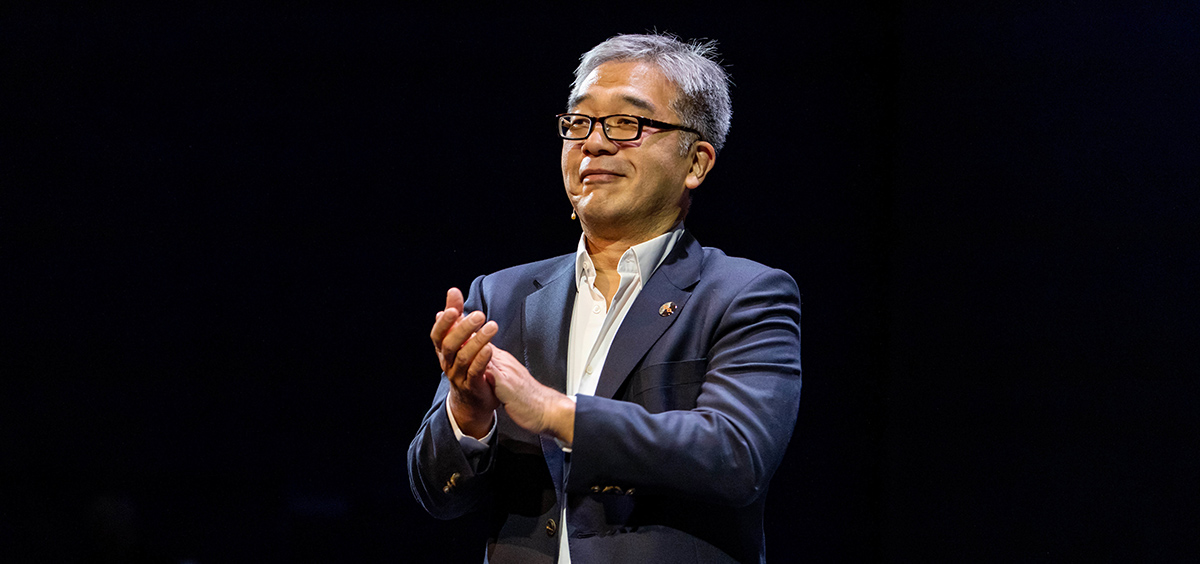

This is the story of my moonshot. One I have spent almost two decades using my philanthropic capital to tackle head first, and the campaign that for the last five years has given me a vehicle to do so, Clearly.

Clearly is a global campaign to change perceptions amongst policy makers and government leaders. To persuade them that vision is not just a low priority health issue but the golden thread to achieving many of the Sustainable Development Goals, to which they have already committed. To not be blind to the issue of vision correction.

It is not a journey that is complete. A billion people around the world still lack access to a simple pair of glasses. But today, we have achieved a huge milestone towards that goal, having spent over five years rattling the cages and spreading our message far and wide. On July 23rd 2021, the General Assembly of the United Nations passed a resolution entitled Vision for Everyone, committing member states to achieving that goal.

With this global body and momentum behind us, I am confident that in the years to come, my moonshot will be achieved and we will have a universal solution to uncorrected poor vision. My hope is that we can do this by the time the first person walks on Mars, so everyone in the world will be able to see it.

This is the story of my journey to help the world to see clearly.

BUILDING A DOMAIN EXPERTISE

Any great moonshot not only takes capital, but the building of a domain expertise. You cannot say that you want to ensure everyone on this planet has access to vision correction, and simply throw money at the problem.

This is the mistake that many philanthropists make. Rather than investing time into learning about the issue they seek to address, they simply sign a cheque and hope that the organisation or person they have donated to does the rest and puts it to good use.

What a waste this is. Donating money is a pious gesture, but not one that can ever lead to real world-shifting change, no matter how many zeroes are at the end of the cheque. What many do not realise is that philanthropists have a superpower to take financial risks that governments and corporations – beholden to taxpayers and shareholders respectively – cannot.

Why? Because these institutions are agents of capital, not the owners of capital. Philanthropists, whose wealth is beholden only unto themselves, have a much greater freedom to accept the consequences of setbacks and failure.

By embracing a risk-taking mindset to deploy risk capital on new ideas and persevering and learning from setbacks to build domain expertise that improves the ratio of success over failure –– moonshot philanthropists have the ability to privatise their failures and socialise their successes for paradigm shifting public benefit.

In my life, I have been blessed to be able to deploy this superpower privilege. And inspired by my father – who spent his later life giving back to the communities in and around where he grew up in Qidong, China, building vital infrastructure – I have committed to pursuing positive systems change as a responsible steward of family wealth.

Like JFK, I do this not because it is easy, but because it is hard. At no point on my journey have I ever expected to make a difference overnight. That is not how you deliver change. You have to be prepared for setbacks and failure, to learn from these and apply the resulting lessons.

Failure is a strong word. Despite my years advocating for the positive power of failure, I find it difficult to say about any of my ventures that they have failed. But admittedly, the first campaign I embarked upon investing in in the vision correction space was in many respects, a failure.

The venture was an ingenious invention: a pair of spectacles with adjustable lenses, which could be altered depending on the strength the wearer needed.

For me it seemed a game-changer. There are 2.2 billion people around the world living with uncorrected poor vision and for most of them, a simple pair of glasses would address this: in this case, adjustable power lens glasses.

But there was not the appetite or momentum for this solution to take hold. We went to the World Bank for funding and were met with a less than lukewarm response. Vision correction was not a perceived priority in the same way as life and death issues such as disease, hunger and poverty were.

In a 2013 organisation chart all five of the World Bank’s most senior figures wore glasses. You would think that they would have understood the urgency, but no. Their vision impairments were corrected and it was something they took for granted.

They had therefore failed to connect the dots. They had failed to realise the urgency of the vision correction question. For example, some agencies will fund adult literacy classes in Africa but most people over 35 living in these areas have poor vision with no access to vision correction and glasses.

How can they learn to read if they cannot see?

This was the first obstacle we came up against, when we realised the global agency for risk was too low and that this venture, on its own, was not viable. Far more work would have to be done at a grassroots level to demonstrate not only that billions live with poor vision, but that addressing this was a global necessity.

This failure only spurred me to invest more into this issue, to continue developing my domain expertise and try to make a success of whatever came next.

What came next was Vision For A Nation (VFAN). This was a charity I founded, based out of the UK – with one clear goal: to deliver universal eye care to the entire nation of Rwanda.

We funded the development of a protocol to train nurses to test for vision correction, eye disease and allergy, in collaboration with the Rwandan Ministry of Health. We trained 2,700 nurses on our screening protocol and sent them to screen Rwandans and dispense glasses to those who needed them, at a price of US$1.50 to every one of the country’s 15,000 villages.

The key innovation here was developing a “good enough, not perfect” screening that eye doctors in developed countries often monopolise through regulation. This was not about delivering perfect vision to everyone with bespoke glasses prescriptions.

The result? Rwanda became the first developing country to offer universal access to vision correction.

VFAN continues its work today, with its next focus on delivering affordable eye care to Ghana.

Rwanda was a success, but if we were to continue tackling this issue one nation at a time – at the same sort of speed we did this in Rwanda (around four years), it would take a millennium to address every country.

So, what next? Continue tackling this one country at a time and hope momentum picked up?

No. You have to learn from your failures and of course, you have to learn from your achievements. You have to always think about what you can do to accelerate progress and double down on any success.

I just did not immediately know what that acceleration would look like.

A NEW CAMPAIGN, A NEW CHALLENGE

In 2015, I met Greg Nugent, the co-founder of Inc. London. He had been the marketing chief of the 2012 London Olympic and Paralympic Games, and after sharing the various strands of my vision journey, I expressed my frustration at not knowing where to take it next. Greg said he could help me to knit the various strands of my vision correction journey into a coherent story. From there, the next stage would present itself.

I attended a later meeting with Greg at the Inc. offices in London, alongside his business partner, former UK Government spokesperson Godric Smith, and the journalist and former Treasury adviser Catherine Macleod. It was a session Greg sold to me as a brainstorming session, but felt to me like an interrogation by Scotland Yard to assess my credibility!

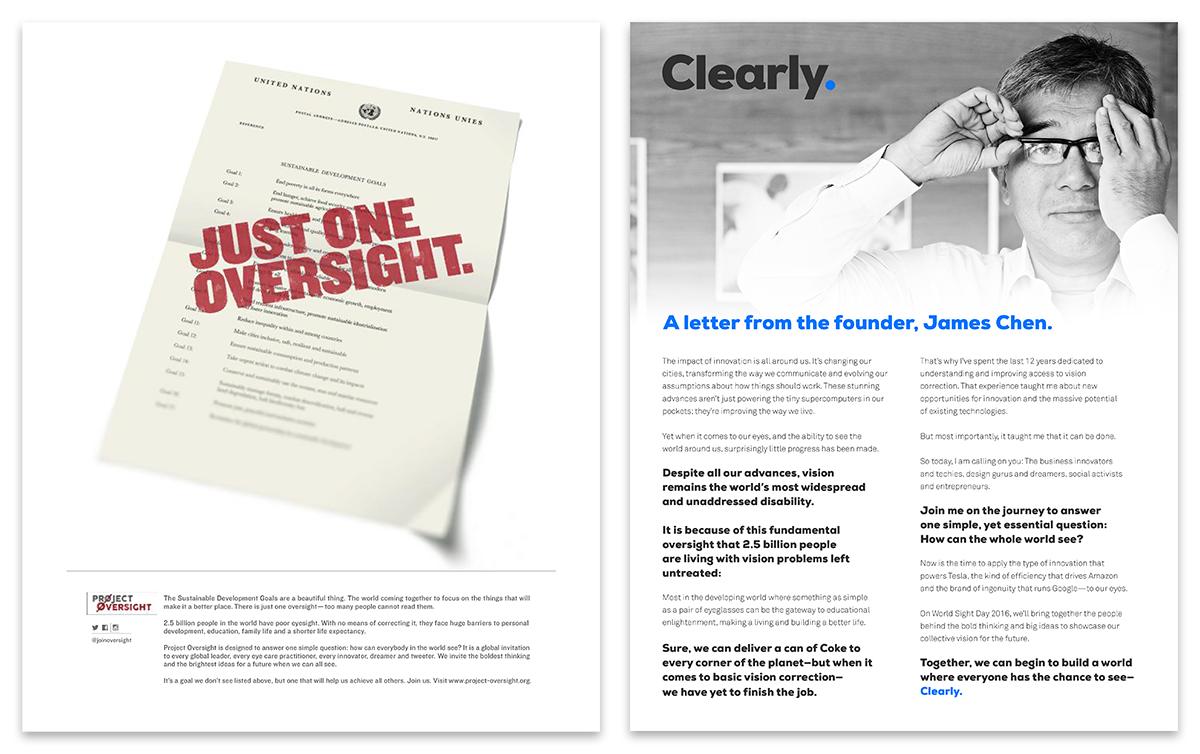

Their advice was to bring all of my work under one banner of ‘universal access to vision correction’. I had so much going on in my mind, all disparate thoughts and campaign ideas, and in five minutes they had helped me to pull it all together – narrowing down my multiple visions into one clear objective. Started as Project Oversight with an advertisement in the New York Times on 24th September, 2015, three days before the UN adopted the Sustainable Development Goals, in early 2016 the Clearly campaign was born.

The idea of universal vision correction was intimidating in many ways. I had always known this was what I had wanted to achieve, but it was only in those early discussions with Greg and his team, and the first weeks of what would become the Clearly campaign, that I fully understood how much work there was to do.

Greg had warned me at the outset that what we are trying to achieve was extremely high risk and his role was to advise on how to avoid a “boil the ocean” trap, by harnessing talent to make the biggest impact with the limited available resources.

What gave me increased confidence was what I was seeing around me at the time. The very faint vision correction drumbeat was growing.

There had been the nascent (but ultimately doomed) Pantheon initiative by a group of top global vision NGOs in partnership with the IAPB, to commission a global vision campaign. Meanwhile, VisionSpring founder Jordan Kassalow had an idea for EYElliance – to which I donated US$50,000 of seed money.

There was no competition between us – we all had the same goals, just different approaches to getting there and I was happy to support the right pathway to success, whether that was mine or theirs. The challenge was to socialise the issue of access to vision correction beyond the community of professionals engaged in the eye sector and into the outside world.

For Clearly, our initial approach was to create a public facing campaign, raising awareness of uncorrected poor vision through social media and targeted activations.

We soon realised this was not working. It was like throwing rocks into an ocean, creating only quickly dissipating ripples with no discernible impact.

The realisation that we needed a new approach also came through a set of activations called the Clearly Labs. These facilitated workshop discussions aimed to bring together world-leading eye care and technology experts, as well as designers, innovators, NGOs and corporates – all offering different perspectives on how to solve the problem.

The Clearly Labs were facilitated by a service provider we engaged in Austin, Texas, who specialised in teasing out audacious solutions to problems. They took hypotheticals and looked to find the moonshot ideas that could address these.

In theory, this was the right approach. Universal affordable eye care was a moonshot goal and Clearly the moonshot campaign within that. But what we realised was that we had facts to back up what we wanted to do from our experience with VFAN. We were not dealing in hypotheticals anymore. The mistake that we made therefore, was failing to frame our goal or the objectives of these Labs correctly.

What we should have done was use the Lab sessions to flesh out what the campaign was. What were our objectives? Who were our targets? Where did we want to be in five years? Instead we spent countless hours posing audacious solutions to an unclear end goal. We had some impressive minds around the table, but we were unable to answer why we were leading this campaign.

But while the Clearly Labs did not produce the results we desired at the outset, it was another learning curve that we could take forward. The one clear lesson that came out of the failure of the initial social media campaign and Clearly Labs was that we needed to refine our thinking and shift our focus towards policymakers. This learning – born from painful and expensive setbacks – paved the road to eventual success.

After establishing that we had to breakthrough with policymakers before the public, we had to test their appetite for change. This meant putting ourselves out there and getting Clearly onto platforms where our aims could be heard by the influential people who could help us to achieve them.

The World Economic Forum (WEF) in Davos presented the first opportunity to do this. Alongside our new team members, Will Straw, Simon Darvill and Charlotte Todman – who joined us from the ‘Britain Stronger in Europe’ campaign – I attended the 2017 summit determined to put Clearly on the map.

From our perspective, if you were laying the foundations for a global campaign, being at WEF meant you were serious.

What we did not fully appreciate was the noise that surrounds Davos. And quite simply, we got lost in it. Philanthropy is but one of a myriad of agenda items on the table and vision correction at that point one of the smallest cogs in the philanthropy wheel. We were at the very bottom of the food chain.

Perhaps we were too early. We were not quite ready for the chaos of WEF and it certainly was not ready for our small, early-stage campaign. But being there allowed us to assess the lay of the land, setting us up well for our own summit later that year.

Our idea was born as the ultimate culmination of the Clearly Labs, to host our own Davos – or Burning Man even – where vision correction would be the one and only agenda item. The plan was to bring the greatest technologists, CEOs and philanthropists to our summit, and encourage them to see the value in universally affordable eye care. We wanted to attract a high net worth audience and inspire them to invest in the cause and its solutions.

We looked to Silicon Valley, knowing many of the best technology entrepreneurs could well offer insights and solutions. Booking out the renowned Amangiri resort in Utah – with a non-refundable deposit – we aimed to get the West Coast’s best minds around the table.

Again, the reality was different to our imagination. The disappointment of Clearly Labs and the initial social media campaign meant that traction was still not there to attract luminaries out into the Utah desert for a campaign they know little about. And so to my disappointment, Greg recommended that we cut our losses on this initial attempt at a summit..

I look at this as one of the key moments in the history of the campaign. A low ebb and a turning point when we could have given up, but instead persisted.

We had been operating for under two years and we had pow-wowed with some of the most influential minds around at our Clearly Labs and at WEF. And yet despite our efforts, we could not get momentum behind our campaign. Vision correction was not breaking through to the public or policy consciousness. We were one of several campaigns and in many ways, each of us were floundering. Perhaps it would have been better to pool my resources and efforts with one of them?

I did not want to give up, but the challenge was that this was costing me and my family a lot of money with very little to show for the investment. It was also becoming extremely difficult to benchmark success, which was a moving target. As Mike Tyson famously said of boxing: “Everyone has a plan, until they get punched in the mouth.” We kept coming up with targets, but were continually being punched and having to change our strategy.

As a team, we felt we had to give it one last go. We knew people were interested, we just had to have a clearer goal to aim for and we had to bring people together to thrash it out what this was. If not at Amangiri, then somewhere else.

BUILDING MOMENTUM

The idea we came up with was a summit in Murano – an island just north of Venice. Famed for its glass-making and reputedly where eyeglasses were first made 700 years ago, it seemed an appropriate spot for our conference on how we could make glasses affordable to everyone on earth.

More accessible than Amangiri, we were able to attract the right people to have the right discussions. We brought together leaders of the eye care sector from around the world, along with influential campaigning figures like Kirsty McNeill from Save the Children, Comic Relief’s Kevin Cahill, and Downing Street’s former director of communications Alastair Campbell.

In many ways Venice was the ultimate Lab – it had a clear aim that had been missing from previous Clearly Labs – where could we take the campaign to make an impact on policymakers?

Throughout the three days, Venice became a hyper-brainstorming event with an electric energy. We established vision correction as the ‘golden thread’, running through all of the SDGs – something that could power global leaders to achieve them. It was a memorable intervention from Godric Smith, and one that still remains in our campaigning work today.

It was the moment that vision correction went from a health issue, to a development one.

Delegates bounced off each other and worked together long into the evening, discussing the issue at hand and ultimately delivering the answer we had been looking for: CHOGM.

The Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM), held biennially, was set to take place in London in 2018 with all 53 leaders of the Commonwealth nations set to be in attendance. With many of these nations in the developing world, by putting vision correction on the agenda, we could have direct access to many of the countries we wanted to target, as well as the collective power of the Commonwealth behind us.

For perhaps the first time since coming up with the idea to campaign for universal access to vision correction, it felt like we were onto something big. It was the first time we could really harness and anchor all of our ideas onto one clear goal and it created an incredible excitement in Venice.

I did not know if it could work. Perhaps, like had been the case at the World Bank and WEF, we would be drowned out by the noise of other issues. But we finally had a specific target – one that was worthy of our aims. It focused our minds and would pave the course towards achievement.

Coming out of Venice, we had a plan. One that would be a huge challenge but with a talented team and a single objective, we felt we had a decent shot at success.

What I had not realised in those early years of the campaign, was that within any moonshot you cannot simply have your end goal. You need to have smaller objectives along the way and a strategy to achieving each. NASA did not simply build a rocket and send it to the moon to hope for the best. It took two space programmes – Gemini and Apollo – and dozens of test flights, spacecrafts and smaller missions before Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin set foot on the lunar surface.

You therefore need a perfectly formed team around you. One that offers all possible perspectives on where you are going and how you get there. In many ways, I was the dreamer and Greg’s team took a similar approach. But equally important were the strategic thinkers helping us to ground what we were trying to achieve in reality.

Dr Graeme Mackenzie, a trained optometrist and academic, whom I had worked with from my very earliest involvements in the eye-care sector, was key to this. He has for years been my go-to-guy for domain expertise, research and just about anything else. His work has helped to frame our mission in the facts that have led vision to be seen as a crucial development issue. With the team at Inc., we had the campaigners but I would never have felt as confident to move forward if not for Graeme’s support in terms of tools, figures, connections and validity.

And alongside me, throughout the entire journey, has been the chief executive of my foundation, The Chen Yet-Sen Family Foundation and Clearly’s Asia Lead, Jennifer Chen. Her role has been to watch our figures, and to ensure that we have been able to fund everything we want to achieve and that my capital is being put to its best use.

This has never been a case of holding us back, but making sure that our velocity is not such that we fly out of orbit. Because a moonshot when done right is not something intangible, it is the art of the possible. But without discipline and realism, our goal would remain just that – a goal. Jennifer made sure that even in our most challenging moments, we remained focused and took the small steps that would lead to our giant leap.

Universally affordable eye care was our moonshot. Clearly was the vehicle to take us there. CHOGM would be the equivalent of putting our campaign into orbit for the first time after several aborted launches.

But to get our idea onto the table at CHOGM, we had to give them a blueprint for what we wanted to achieve. The question was how could we engagingly capture our aims in a way that demonstrated this? We had to prove this was not a speculative idea, but one that leaders could latch onto.

Greg’s idea was to write a book. This would outline the cause and a radical action plan for tackling the four problems we sought to address. What we called the ‘Four D’s’: Distribution, Diagnosis, Dollars and Demand. Phil Webster ably ghost wrote the draft of the book and Will Straw excelled as the book’s editor while tirelessly and brilliantly leading the CHOGM advocacy effort. Graeme was equally crucial to helping us get the book written – proving to be our ultimate fact-checker and inspiration.

The book forced us to think hard about what we were trying to say, to crystallise our views, and to generate clarity within the sector. It identified the obstacles to spreading good vision across the world and then set out the solutions, alongside the stories of people who had been helped by the simple provision of glasses. It gave us credibility and a stamp of authority that we could take to CHOGM, proving crucial to making our case to put vision correction on the agenda.

Our external communications team at Seven Hills were central to the book’s success – facilitating our message and executing a press strategy. It is one thing to write a book, another entirely to get people to read it. Led by Charlotte Hastings and Nick Giles, the team engaged the media with the book, ensuring a constant stream of publicity that helped bring it to people’s attention.

Writing the book was not only important for the campaign’s momentum, but for my own. It really committed myself and the team to examine the case for supporting our movement in depth, and while the process of writing the book was long and painful, it was ultimately incredibly cathartic and brought our team even closer together.

After the book’s publication, I think the eye sector began to sit up and take notice. They knew we were not just amateurs mucking about, but taking this incredibly seriously.

With our book – our manifesto in many ways – in hand, we began an intense lobbying effort alongside other key organisations in the sector, forming ‘Vision for the Commonwealth’, to secure our aim of putting poor vision on the CHOGM agenda. Working with the Committee of the Whole (COW), which screened resolutions to go before the main CHOGM summit, we used our contacts in government and the civil service to advocate for our place at the table.

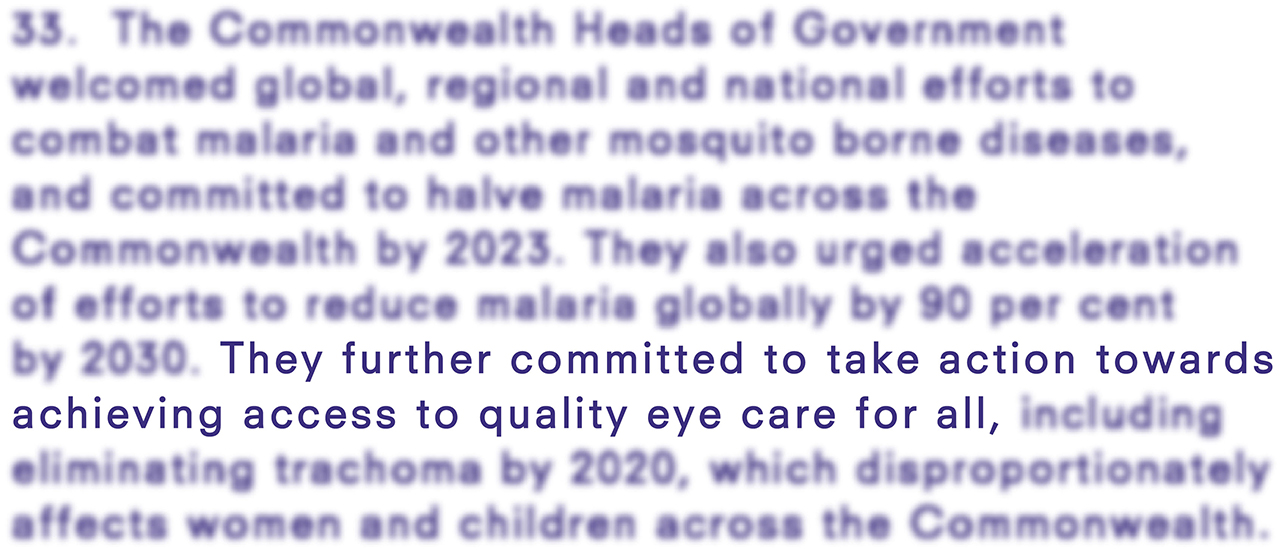

And we succeeded. Three years on from my first meeting with Greg, we had finally made a real breakthrough. For the first time, the Commonwealth heads of state would sit down and discuss vision correction.

In April 2018, we went to London and made our case to these leaders. We explained how vision correction was a golden thread to the SDGs, how many hundreds of millions lacked access to a simple pair of glasses, and the productivity gains that could be secured worldwide by making them universally available.

This time our voice was heard. All 53 leaders committed to achieving the aim of ‘quality eye care for all’. It was the first time in history that the global crisis of poor vision had been formally recognised at a meeting of world leaders.

It was also validation. Validation that beyond the eye sector, people did really care about this issue and that it made sense to be on the development agenda. This would become our calling card to the development community and to other global world leaders – allowing us to take the issue further still, to the World Health Organization (WHO), the United Nations (UN) and individual governments.

By making this commitment, we have the authority to hold all 53 of these leaders to account. If they fail to act then we will hold their feet to the fire until they do. And while the COVID-19 pandemic put a pregnant pause on CHOGM 2020 in Rwanda, which we hoped would be the next great stepping stone to achieving progress within the Commonwealth – coming to the very country we successfully achieved affordable eye care for all with VFAN – we are confident that we can continue to make our case.

With governmental backing achieved, what we needed next was irrefutable evidence of the impact of glasses on achieving the SDGs. If we had this, then we knew we could turn back to the Commonwealth and say: “You have committed to this, now here is the proof of what can be achieved.”

We commissioned a study of agricultural workers in India’s tea-picking district of Assam. In a controlled study of more than 750 tea-pickers, half were given a simple pair of reading glasses – like those you can buy cheaply, over the counter in many developed countries – and half did not. Before the trial, not one of the trial’s subjects – all of whom were over 40 – had glasses.

The results were unequivocal. Workers with glasses plucked around 5kg more tea each day than those without — a 21.7 per cent increase in productivity. Tea-pickers over the age of 50 recorded even bigger gains, at 31 per cent. With the support and connections of Dr Graeme Mackenzie behind us, the study was peer-reviewed in Lancet Global Health, and powered further momentum for Clearly.

The team at Seven Hills also drove the study into the public’s attention, securing coverage in the Financial Times, The Economist and the BBC. The research showed the real productivity gains of good vision and proved to be a valuable advocacy device, enabling us to move the argument on from health. Again, we made the noise and got ourselves noticed.

MAKING A GLOBAL IMPACT

Eye care sector – engaged. Book – written. World leaders – committed. Evidence – irrefutable.

From the bleakness we were feeling at the start of 2017 to the exuberance we felt at the end of 2018, the change was astonishing. The progress we had made demonstrated so much to me about the power of a moonshot to capture imaginations. We were finally rising above the noise.

Alongside CHOGM, in 2019 the WHO published its World Report on Vision. This provided evidence on the magnitude of eye conditions and vision impairment globally, drawing attention to effective strategies to address eye care, and offering recommendations for action to improve eye care services worldwide.

But with all this success, we still faced challenges. Our own event, Sightgeist, hosted at London’s Science Museum in 2019, was an audacious project that ultimately did not justify the cost.

With the broadcaster June Sarpong MBE MC’ing the event, Sightgeist convened leading scientists, technologists, campaigners, innovators and thought leaders. Keynote speakers included Professor Brian Cox OBE FRS, and Lord Bates from the Department for International Development, who announced an extra £9.8 million in funding to assistive technologies globally. The show, however, was stolen by young Lowri Moore, who captivated the audience with her appeal to Disney to give us a princess wearing glasses.

It was a superb event with lively speakers and a great message, but its expense put a lot of pressure on us to produce Venice-level solutions and ideas on the day, which we ultimately did not have the time nor audience to. Jennifer particularly felt that we had moved away from the event’s goals at the outset in favour of something much bigger and flashier – visually impactful – but far more expensive and ultimately less effective than the small-scale event we had initially planned.

One thing it did however, was bring together our stakeholders from the UK and the US into one room. The latter tended to be more excited by market-driven solutions and the former were traditionally more institutional-focused. Sightgeist allowed them to meet one another for the first time and begin conversations around how these differing approaches could become better aligned.

By this point, it was clear that Clearly and the issue of vision correction was a part of the global conversation. But what we needed was time to have that conversation. WEF and Sightgeist did not produce the results we wanted because we felt either drowned out or constrained by time. At both Venice and CHOGM, we had the space and audience to make our case.

That was why I was initially sceptical about a proposed initiative on the UN General Assembly. I felt it likely would be a repeat of Davos and our first trip in 2017 did not disabuse me of this idea. Our ultimate aim was to get a UN resolution on poor vision, committing all the member nations to solving this cause. While we hosted an excellent breakfast roundtable with speakers including former Rwandan Health Minister and local champion of VFAN Dr Agnes Binagwaho, and UK development minister Baroness Sugg – which was attended by 17 guests including several low-level diplomatic representatives – the politics and bureaucracies of the UN overwhelmed us that first year.

I did not feel like returning was worth it. Will Straw convinced me otherwise. He was introduced to Jonathan Rich who had worked for the United Nations Foundation and knew his way around the UN’s byzantine world. With his guidance and Will’s political nous, we were able to make our voice heard through an intense lobbying effort.

Our campaigning caught the attention of Ambassador Aubrey Webson – representative of Antigua & Barbuda, who himself is legally blind – and he became an important ally at the heart of the UN. Well respected, particularly on the issue of vision and its impact on development, he championed our cause and continues to do so to this day.

As a result of this work, a ‘Friends of Vision’ working group was created under Ambassador Webson’s leadership, with the Ambassadors of Ireland and Bangladesh, Geraldine Byrne Nason and Rabab Fatima, joining as co-chairs. Over 70 countries have now taken part in the group and it has held regular events including a hugely successful vision screening in the lobby of the UN in November 2019.

A further group meeting held in February 2021 displayed new research from the IAPB and Lancet Global Health, showing that eye health is essential to meeting the SDGs. This event was attended by the President of the UN General Assembly, Volkan Bozkir and several other key figures. Here, the Friends of Vision co-chairs tabled a draft of the UN’s first ever resolution on vision, which addresses the global issue of unaddressed poor vision and its links to the Sustainable Development Goals.

The support was unanimous and clear at that meeting, where Ambassador Bozkir said: “Trust that you have my complete support in your efforts to include vision in the upcoming discussions around Universal Health Care, and in the draft resolution on eye health.”

Even with this support, like everything, the process to ratify this resolution took its time. But as they say, the best things in life really are worth waiting for.

On July 23rd 2021, the resolution was passed unanimously by all 193 countries of the United Nations.

Just reading those words is, for me, incredibly powerful. Our small campaign is now a global movement that has aligned the entire world around a single target of ‘eye care for all by 2030’. Countries are committed to ensuring full access to eye care services for their populations, and, to support global efforts, to make eye care part of their nation’s journey to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals.

The resolution also creates new expectations for international financial institutions and donors to provide targeted finances, especially to support developing countries in tackling preventable sight loss. And for the United Nations to incorporate eye care through its work, including with UNICEF and UN-Women.

And perhaps most strikingly, not only is it now clear that eye care is a golden thread to the existing 17 Sustainable Development Goals, two new goals are set to be added at the next review of the SDGs, with specific targets for eye care.

The plan will mean that by 2030, those 1.1 billion people currently living with sight loss, will have access to support and treatment.

As incredible as the passing of this resolution is for our movement; as far as we have come in six years, the work has only just begun. To secure eye care for all by 2030, governments have to resource the plan.

We have four recommendations for governments to ensure this succeeds. Firstly, new financial investment and resources to provide eye care services for their populations at home. Secondly, to implement a domestic national strategy for eye care for all, across all government departments. Third, they must incorporate eye care into their country’s journey to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. And, finally, they must adopt the recommendations of the World Health Organisation’s ‘World Report on Vision’ in full.

I had hoped when we first came to the UN that we could one day get a resolution. Sometimes, I was worried it would not be possible. But thanks to the tireless work of Ambassador Webson and the rest of the Friends of Vision working group, plus our Clearly team, we now have it.

And suddenly, what seemed like a disaster – the postponement of CHOGM – has become a blessing in disguise. We now head to Rwanda with a UN resolution on vision correction that will only strengthen our case for more urgent action.

The true mark of entrepreneurship is to turn every challenge into an opportunity. With the world coming out of COVID, there may be competing health priorities, but there is also an urgent need to improve productivity to bring our economies back up to speed.

Our message is this: vision correction can help. We know the impact of glasses on productivity, particularly in the developing world and so this is low hanging fruit for nations looking to speed up their recoveries. No invention is needed, no vaccine has to be developed, we have had the solution for more than 700 years. I hope this is something global bodies recognise as we emerge from the pandemic.

The UN, WHO, CHOGM. Three of the world’s most powerful international bodies. And all of them now consider the issue of poor vision crucial to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals, to which they have already committed. If you could have told me we would have achieved this when we were turned away from the World Bank with that first venture so many years ago, I am not sure I would have believed you.

I feel tremendously lucky to have had such success with Clearly and if not for the persistence of my team, fantastic partners and stakeholders, and some lucky breaks, I could have spent a lot more money and time with fewer results to show for it. It is a humbling thought.

As the saying goes, luck accrues to those who are prepared to receive it and make use of it. We have had plenty of luck on our journey, but we have certainly made use of it too.

A NEW CHAPTER FOR CLEARLY

The last year has been monumental for Clearly as we continued reaching new heights, even in a changed and increasingly virtual world.

We launched the Glasses in Classes campaign to ensure access to glasses in every school in the world, to give children the best start in life. With statistics showing that 500 million children could be living with myopia by 2050, this is crucial in achieving universal childhood literacy.

This campaign was launched with a ‘Vision for the Commonwealth’ event held at St James’s Palace in February 2020, hosted by HRH Sophie, Countess of Wessex. Our message for the event was for Commonwealth leaders “to show vision on vision” by tackling what we identified as a vision crisis amongst school children. Our call was for world leaders to commit to offering sight tests, affordable glasses and other treatments to every schoolchild in the Commonwealth, giving them the best possible start in life.

We aimed for this event to set us up for CHOGM in Rwanda – with a powerful image of attendees including the Countess of Wessex herself putting her ‘Glasses On’ to show support for the Glasses in Classes campaign. I felt that to be able to attract the attention and patronage of the Countess of Sussex was a validation of our idea and proof that our message was cutting through.

The postponement of CHOGM shortly afterwards due to the pandemic, was therefore a disappointing setback. But we used our agility to pivot to another major piece of campaigning work, for World Sight Day in October 2020. In a special collaboration with world famous authors and celebrities, Clearly released an anthology of children’s stories and illustrations, featuring many famous children’s characters reading and wearing glasses, to raise awareness of the Glasses in Classes campaign.

Celebrities and other contributors, including Sir Michael Morpurgo, Billie Jean King, Quentin Blake and Cressida Cowell, read bedtime stories from the book as the sun set in their time-zone, an ambitious project that delivered positive results.

Alongside the book, we launched a new piece of research that found more than 50,000 children in the UK were at risk of poor vision or sight loss. If not treated early enough, amblyopia or ‘lazy eye’ can cause permanent vision damage. We found that there is a postcode lottery across the country as to the standards of eye care screenings – with 250,000 four to five-year-olds missing out on screenings entirely and a further 300,000 screenings not matching Public Health England guidelines.

Our campaigning began to advance the provision of eye care in developing countries. And yet in Rwanda, Ghana, Botswana and others, work has been underway for some time to achieve universal affordable eye care. If developed nations like the UK do not act soon to respond to their challenges, they could well fall behind.

With lockdowns leaving many pupils learning remotely and sat at computer screens all day, more children than ever became at risk of developing vision impairments. It is crucial that we continue to act quickly.

Our next step is to implement the world’s biggest ever research programme into the life-changing power of glasses. Research will take place in seven countries: the USA, China, India, Bangladesh, Vietnam, Indonesia and the UK. Dr Graeme Mackenzie will of course, remain closely involved in the research.

We are set to produce the gold standard in evidence of the link between vision correction and the SDGs. By investing in research linking vision correction to quantifiable productivity and education improvements we can convince governments and employers that it is in their own self-interest to provide eye tests and glasses for all.

Our ability to scale up our work further and faster than ever before, is a result of perhaps the most monumental development in our campaign’s history. In January 2021, Clearly merged into the IAPB, the network of over 150 members working in international eye health and leading global advocacy body for the sight sector.

It is a sign of the growing strength of the sector and the progress that has been made on the issue over the last five years, that this merger has come about. The move is designed to combine our two organisations’ advocacy and campaigning expertise and bring renewed pressure on global actors and governments to end the vision crisis.

With the power of the IAPB and its members behind us, we can continue our world-changing research apace and place greater pressure on the global bodies like the UN, CHOGM and WHO, to continue to make progress for the eye care sector and follow up on their commitments.

On a personal level, it has been a bittersweet moment for myself and our small team, who took us to this stage. The IAPB is the best possible partner for Clearly and for the vision sector in taking the strides we need to achieve our goals. But it is sad to disband our dream team, without whom, none of this would have been possible, and to whom I am forever grateful.

This is by no means the end of my journey in this space. I am excited to see where the IAPB takes Clearly, but I will not be watching from afar. My role as a global ambassador for the IAPB is underway and I remain a guiding hand on that journey – chairing the campaign’s committee, which affords me the opportunity to continue interacting with some Clearly campaign veterans whom have joined the IAPB.

We can reflect with absolute pride on what we achieved. We put the issue of universal access to vision correction on the global development map and have put this moonshot not only into orbit, but on the right path towards its lunar destination.

To be a campaign with a UN resolution and global recognition were not the metrics that I imagined success to be when we set out with Project Oversight, but in hindsight, what we have done is far beyond our best-case scenario. We have rattled the cages of the highest offices in the world and made it clear that vision matters.